General information

- Open fractures tended to occur with MVAs,

- Closed fractures tended to follow accidents at home.

- Dural lacerations are more common in compound fractures.

Number

- Occur in 7-10% of the children admitted to hospital with a head injury.

- 1/3 are closed

- tend to occur in younger children (3.4 ± 4.2 yrs, vs. 8.0 ± 4.5 yrs for compound fractures)

- as a result of the thinner, more deformable skull.

Location

- Most common in frontal and parietal bones.

Simple depressed skull fractures

- >1 years old

- deeper the depressed bone (> 1 cm),

- the higher the risk of dural laceration and cortical laceration in adults and older children,

- but less clear in neonate and infant populations.

- Surgical treatment

- Indicated

- fragments are depressed to the depth of at least one thickness of the skull,

- intracranial hematoma,

- dural laceration/CSF leak,

- cosmetically deforming defects,

- gross wound contamination,

- established wound infection.

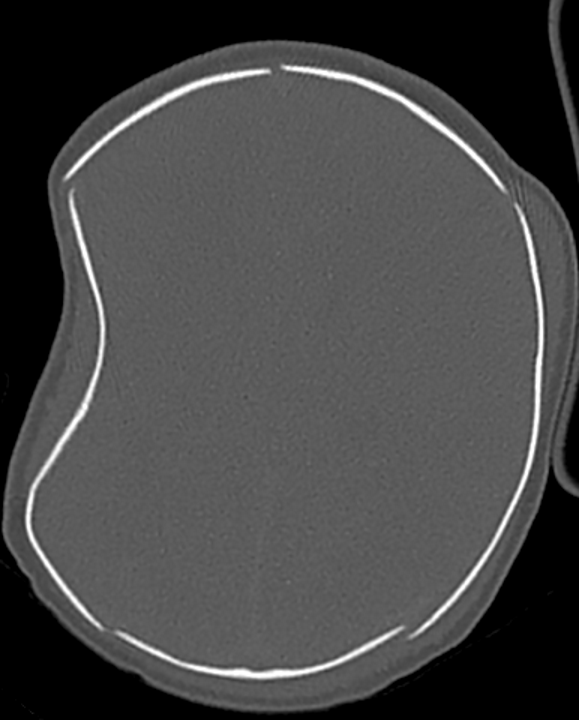

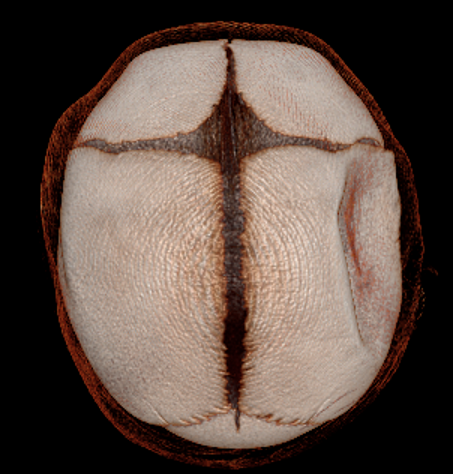

“Ping-pong ball” /Cup shaped fractures

- Depressed skull fractures that occur in children younger than 1 year

- Usually seen only in the newborn due to the plasticity of the skull.

- Commonly after

- Head trauma for post-natal

- Birth trauma for neonates

- A green-stick type of fracture → Outer table is fractured around the periphery, while the inner table fractures at the center → caving in of a focal area of the skull as in a crushed area of a ping pong ball.

Management

- No treatment is necessary when these occur in the temporoparietal region in the absence of underlying brain injury as the deformity will usually correct as the skull grows.

- There was no difference in outcome (seizures, neurologic dysfunction or cosmetic appearance) in surgical vs. nonsurgical treatment in 111 patients < 16 yrs of age.

- In the younger child, remodelling of the skull as a result of brain growth tends to smooth out the deformity.

- Indications for surgery

- radiographic evidence of intraparenchymal bone fragments

- associated neurologic deficit (rare)

- signs of increased intracranial pressure

- signs of CSF leak deep to the galea

- Definite evidence of dural penetration

- situations where the patient will have difficulty getting long-term follow-up

- Persistent cosmetic defect in the older child after the swelling has subsided

- Technique

- Frontally located lesions may be corrected for cosmesis by making a small linear incision behind the hairline, opening the cranium adjacent to the depression, and pushing it back out e.g. with a Penfield #3 dissector.