General

- Aka Di Chiro Type I

Numbers

- Most common spinal vascular malformation

- found in males (80–90%)

- 40 and 60 years of age

Connection

- Direct connection between

- a radicular artery (after it enters the dural sleeve of the nerve root) ↔

- a vein

- Radiculomedullary vein

flowchart TD subgraph s2["Symptomatology"] direction LR n7["Bowel bladder dysfunction"] n8["lower limb neuro deficits"] end A["Arterialized high pressure<br>in radicular vein"] --> B["Back flow into<br>radiculomedullary vein"] B --> C["Back flow into<br>longitudinal spinal cord veins/venous network<br>(responsible for draining the<br>spinal cord)"] C --> D["Congest the spinal<br>cord venous system"] & n3["opening of other<br>radiculomedullary veins"] n3 --> n4["Chronic back pressure"] & D n4 --> n9["Neointimal proliferation<br>(arterialisation of venous<br>flow)"] D --> n6["Starts at the conus and<br>ascend cranially"] n7 --> n8 n6 --> s2 n9 --> n5["permananet change in the<br>veins causing permanent<br>symptoms"] n5 --> n10["Treatment at this point will<br>prevent worsening of<br>symptoms but will not<br>restore modified<br>radiculomedullary veins<br>therefore pt will not have<br>meaningful clinical<br>improvement"] classDef default line-height:1.2,teaxt-align:middle

- due to vascular congestion

- Bladder and bowel problems first then subsequently get sensorimotor deficits within the lower extremities

- Patient may be asymptomatic:

- Drain centrifugally (away from the spinal cord) via the radicular vein --> external venous paraspinal network.

- The external paraspinal network is so vast that it can accomodate this excess blood and do not cause back pressure into spinal cord.

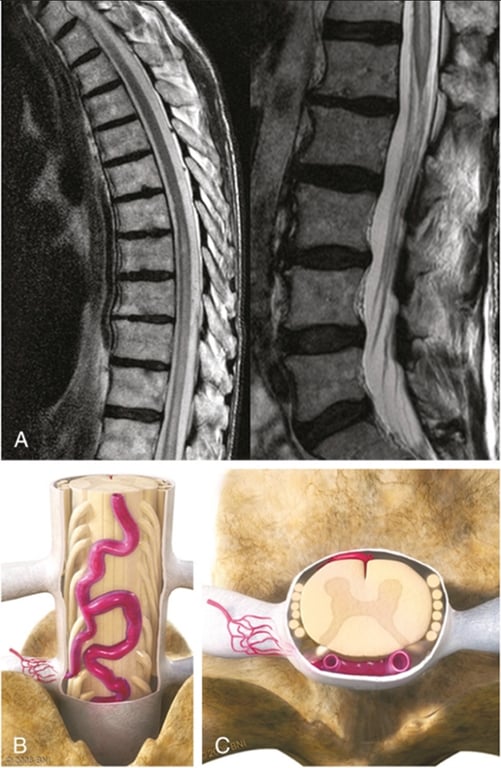

- Images from neuroangio

- typically within the dural sleeve (dural cover of the radicular nerve, usually in the region of the neural foramen).

- Urodynamics are usually abnormal at this stage but there may not yet be enough MRI evidence of congestion to suggest a vascular cause.

- The symptoms tend to fluctuate probably reflecting underlying changes in venous pressures and cord congestion.

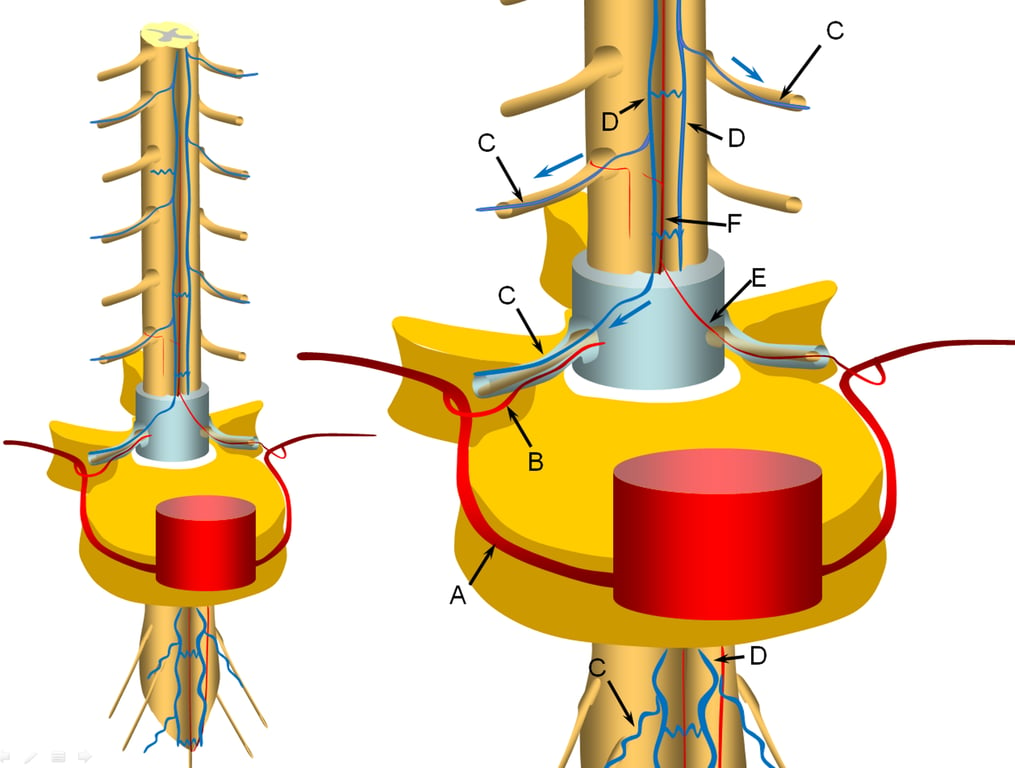

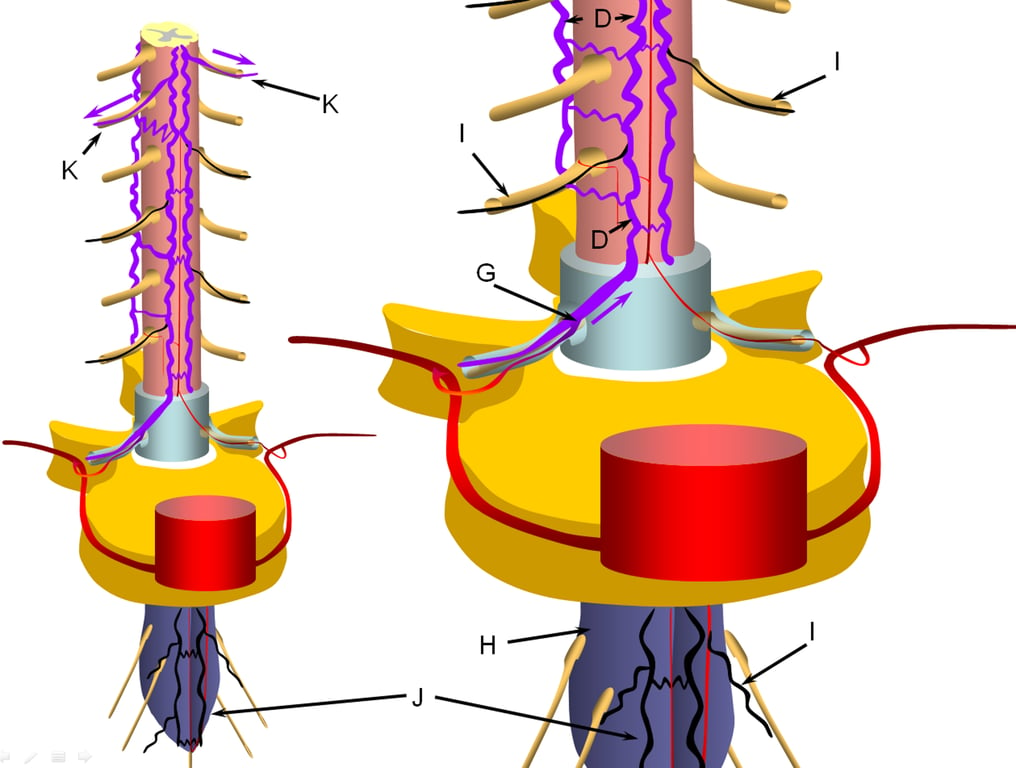

A representative segmental artery (A) gives off the radicular artery (B) which supplies the nerve root sheath.

The spinal cord drainage is conducted through longitudinal spinal cord veins (D) into, which is drained by a radiculomedullary vein (C) in the direction shown by the blue arrow.

Additional radiculomedullary veins are present at other levels, also marked “C”.

Additional radiculomedullary veins are present at other levels, also marked “C”.

A radiculomedullary artery (E) is supplying the anterior spinal artery (F)

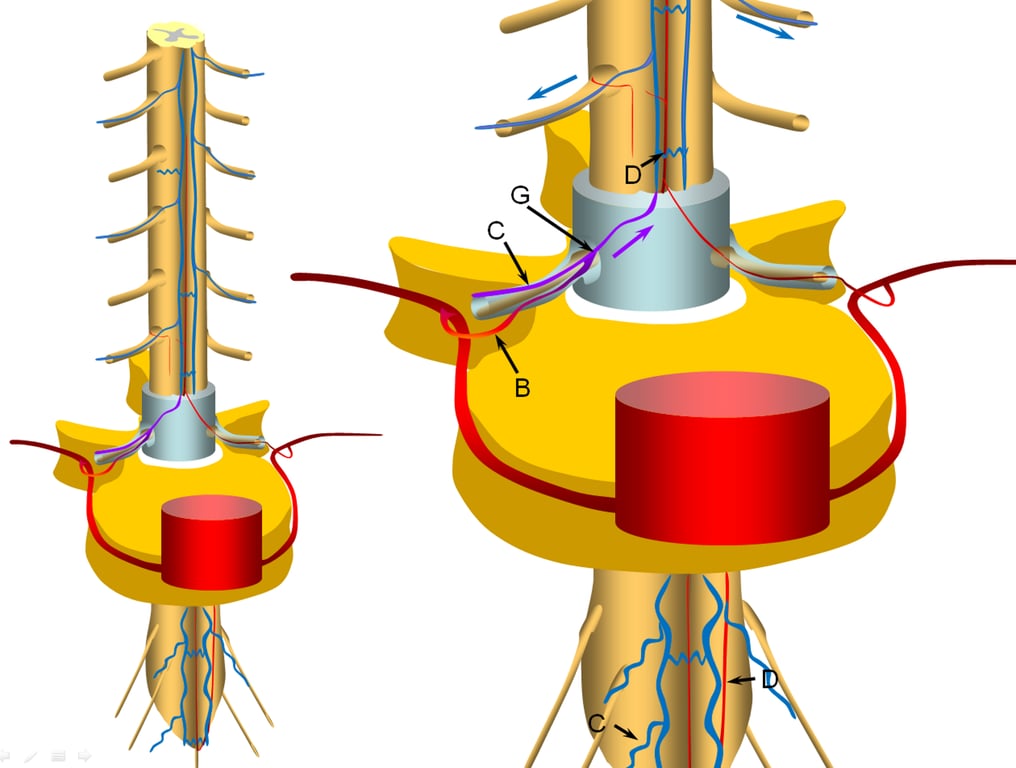

A fistula (G) is formed between the radicular artery (B) and radiculomedullary vein ©

Other sites of fistula are of course possible, but regardless of fistula site, the clinical picture tends to be similar.

Establishment of fistula results in regional venous congestion and reversal of flow within the radiculomedullary vein (purple arrow) which direct fistulous flow into the spinal veins (D) with subsequent egress via other radiculomedullary veins (blue arrows)

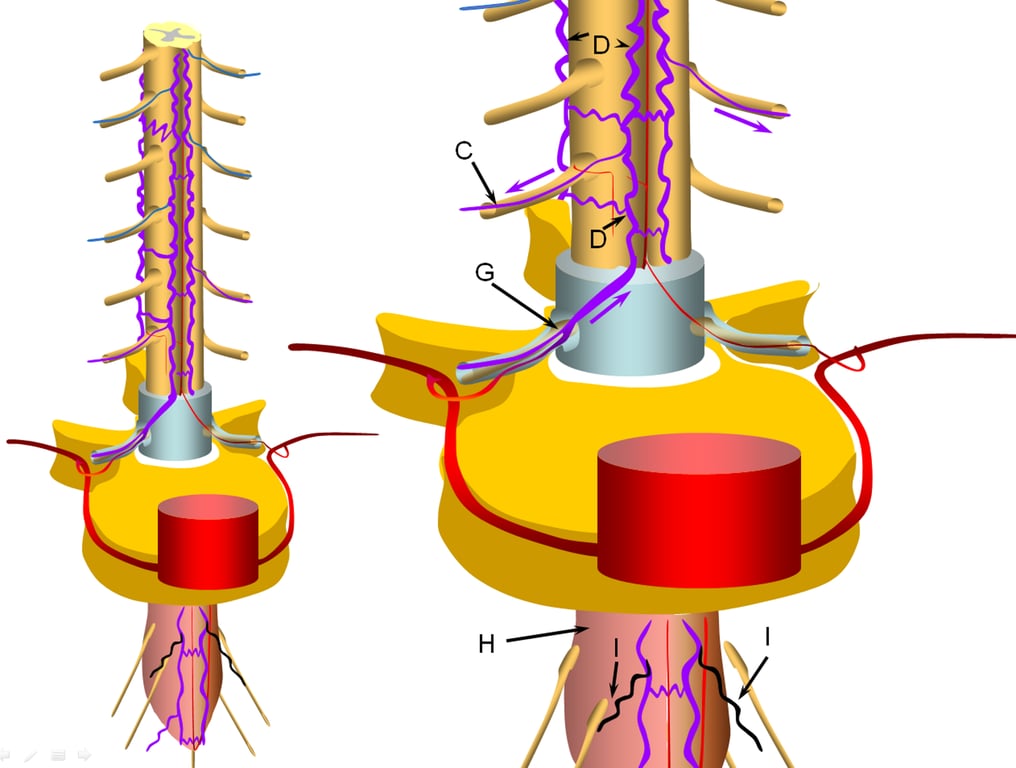

Progressive increase in venous hypertension of the spinal veins (D) result in gradual failure of radiculomedullary veins (I, coloured in black) via thrombosis starting with the most dependent location of conus (H, coloured in redding hue to depict congestion).

The patient typically reports various conus symptoms such as urinary complaints, which can be vague.

The stepwise process of venous outflow failure and subsequent partial adaptation to find progressively higher drainage routes continues until enough radiculomedullary veins fail to enter a more rapidly progressive stage of disease, depicted here.

The fistula drainage is conducted via surviving rostral radiculomedullary veins (K), a large portion of the cord is congested, whereas the lower conal regions may undergo irreversible damage (J, diagrammed in blue). Most patients present somewhere between the intermediate and late stages.

The fistula drainage is conducted via surviving rostral radiculomedullary veins (K), a large portion of the cord is congested, whereas the lower conal regions may undergo irreversible damage (J, diagrammed in blue). Most patients present somewhere between the intermediate and late stages.

Symptoms

- The length of time between formation of the fistula and clinical decline appears to reflect both size of the fistula and eventual failure of the radiculomedullar venous system.

- Medullary veins often anastomose to an extensive network of venous plexi in the coronal plane of the dorsal spinal cord → can be seen in angiography as early draining veins

- The site of the fistula (most often in the thoracic, lumbar, or sacral regions) has no relationship with the patient’s symptomatology, because it is spinal cord vascular congestion, rather than fistula itself, that produces the clinical syndrome

- Slow gradual myelopathy

- Retrograde flow -->

- Venous hypertension / vascular engorgement → local mass effect,

- Venous congestion

- Foix-Alajouanine syndrome refers to subacute, progressive myelopathy due to venous hypertension from a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula.

- SAH (rare)

- Due to

- Spontaneous thrombosis

- Spontaneous haemorrhage

- Cervical (Rare)

- Thoracic/lumbar

- Venous aneurysm

- Venous varicosity

- Trauma, or

- Surgery at venous outflow --> distention of the fragile coronal venous plexus

- Causing sudden acute myelopathy

Treatment

- Microsurgical

- Approach

- Open

- Hemi/Laminectomy

- Minimal invasive approach

- Tubular retraction systems + fibreoptic lighting

- Treating pathology

- Disconnection of the vein the fistulating point (in the region of the nerve root sleeve) will obliterate the arteriovenous shunt (obliterated with cautery)

- Several millimeters of the feeding radicular artery and intradural draining vein may be cauterized, divided, and contiguously excised along with a small window of dura on the root sleeve.

- Excision of the dura is not required to treat the fistula.

- Extradural diathermy (or embolization) of arterial feeding vessels alone may result in transient improvement but are bound to result in the recruitment of other dural arterial vessels and recurrence of the fistula.

- While arterialized the veins of the dorsal coronal plexus are engorged and slightly pink. When the shunt is closed these veins collapse and the pia- arachnoid around them becomes crenulated.

- Adjuncts

- Microdoppler examination

- to confirm normalization of flow in the vein.

- Indocyanine green video-angiography (ICG- VA)

- to confirm normalization of flow in the vein.

- To detect metameric vessels and distinguishing them from arterialized veins

- Endovascular

- Aim

- to get embolic agent to reach the proximal part of the draining vein piercing the dura → ‘point’ disconnection of the arteriovenous shunt

- Liquid embolic agents such as Onyx or NCBA penetrate to the draining vein effectively when delivered transarterially.

- Embolization of arterial supply of the arterial inflow alone will not produce a lasting result

- Circumstances the fistula may not be amenable to endovascular treatment

- Presence of a radiculomedullary artery (or sizable radiculopial artery) giving rise to anterior or posterior spinal artery at the same level as the fistula

- Insufficient length of fistulous radiculomedullary vein “safety” prior to egress into the spinal veins

- Inability to achieve an optimal embolization position

- If, on control angiography, the agent has not reached the draining vein then further treatment will be required.

- This further procedure should not be delayed in hopes the fistula will spontaneously thrombose despite a patent draining vein. --> otherwise clinical deterioration will occur

- Some authors advocate a tentative attempt at embolization at the time of diagnostic angiography.

- Should inform the patient of the small risk of retrograde coronal vein thrombosis which can result in neurological deterioration.

- If cannot endovascular tx, deposit several coils into the segmental artery to mark the location of the fistula and refer the patient for microsurgical obliteration.

- It is important not to decrease fistulous flow during such coiling so as to help the surgeon locate the fistula visually.

- Fistula obliteration rate is significantly lower with embolization, and progressive myelopathy is a risk due to delay in definitive treatment

- Outcome

- Rarely, closure of the fistula leads to an unfortunate deterioration rather than improvement, in patient condition.

- One reason for this decline is posttreatment thrombosis of the spinal veins, which having enlarged far beyond normal capacity and suddenly deprived of high volume fistulous flow, encounter marked venous stasis with subsequent thrombus formation.

- It may thus be helpful to maintain gentle heparinization of the patient following either endovascular or surgical closure of the fistula.

- Bladder symptoms are usually last to improve if there is any improvements at all

- Given where the spinal cord oedema is the greatest

- Baker 2015 N=1112 Meta-analysis

- Surgery obliterated 96.6% of fistulae.

- Endovascular (N- butyl- cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue or Onyx) obliterated 72.2%

- Late recurrence of the fistula was significantly more likely with endovascular treatment

- Complication

- Steinmetz 2004

- Microsurgery: 1.9%

- Endovascular tx: 3.7%

- Surgery vs endovascular for spinal dural av fistula (Type 1 international classification; extradural AVF)

- Goyal et al 2019

- Surgery has lower failure rate and recurrence rate

- Surgery did not have higher morbidity

- Surgery and endovascular had similar improvement

Images